By Rondi Sokoloff Frieder

“I love that part!”

“Really? It didn’t work for me.”

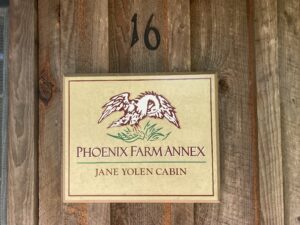

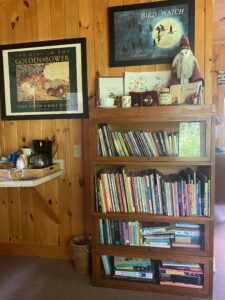

Last summer, I attended “The Whole Novel Workshop” on the idyllic campus of the Highlights Foundation in the Pocono Mountains of Pennsylvania. I brought along a middle-grade manuscript that had been revised numerous times, and got ready to make it sparkle and shine.

Before we got started, one of our faculty members gave us an introductory pep talk. “Just so you know,” she began. “All of you will have to rewrite your books. This is why you are here. But don’t worry, you can do it.” Most of us had to be thinking the same thing: “Maybe some people have to redo the entire thing, but my book is amazing. It just needs a few tweaks and a bit of trimming.” To this I now say, LOL!

Despite my overconfidence, I decided to open my mind to possibility. I listened to the suggestions of my Brain Trust partners and marveled at the insights of our well-published faculty. I threw myself into the writing exercises that revealed twists and turns I hadn’t considered. I reworked my plot. I played around with present vs past tense. And most importantly, I thought long and hard about the crucial themes in this story. What did my protagonist really want?

When I got home, I continued the work. I eliminated unnecessary characters (at least four), I changed the personalities of two of my secondaries, and enhanced components of the story that would make it funnier. Then, after months and months of revising, I gave this new draft to my always brilliant SCBWI critique group, The Story Spinners. My husband and son also volunteered to read the book, and I sent ten pages and a synopsis to an agent who was doing critiques at the RMC-SCBWI fall conference. The book was definitely stronger, but there were new elements that needed to be evaluated. I was too close to the story to know if they were working. While I waited for my readers to plow through the manuscript, I threw myself into another project.

My husband and son also volunteered to read the book, and I sent ten pages and a synopsis to an agent who was doing critiques at the RMC-SCBWI fall conference. The book was definitely stronger, but there were new elements that needed to be evaluated. I was too close to the story to know if they were working. While I waited for my readers to plow through the manuscript, I threw myself into another project.

A month later, the feedback began to roll in. And while there was a great deal of consensus, my readers also had conflicting responses. This was when the “wrestling” part of the revision process set in. Who should I believe?

This is the nature of critique. Some comments will be subjective while others will be quite valid. Here’s the rule of thumb: if something in your manuscript is bothering three or four readers, you must consider making the changes. But, if you really want to keep this section in your book, you must make it stronger. For example, one of my critique partners loves when my main character hears his deceased great-grandfather’s voice in his head. But another reader said it didn’t add anything to the story and that I should cut it. I wrestled with the possibilities. Hmm, what to do? Well, I also love the voice of the great-grandfather. Only this feedback let me know that if I want it to stay in the book, I need to amp it up and make it a more integral part of the story.

There were also sections of the book that were flagged by a reader who had a particular expertise. My sporty son said one of the baseball scenes was unrealistic. Another said a parade would never be in the late afternoon. They both had very good points. I fixed both of these things immediately.

But the most important thing I did as I “wrestled with feedback” was to put the manuscript aside. I did not begin revising for two long weeks. I let my readers’ notes roam around in my subconscious and take shape. I also took a lot of deep breaths! Because getting feedback on your creative work can be extremely overwhelming and downright discouraging. Taking a break from the “noise” helped me get back to work with a more positive outlook. I was also more open to making the changes I was resistant to when I first heard them.

Eventually, I was ready to dig in. I pulled up the line edits and read each and every one. I considered all the possibilities and made choices. I finished the revision. Then I sent it off to one more trusted reader – a person who has not read the entire book. He will see it with fresh eyes. Some of his comments will resonate, some will not. I will wrestle with this. Because this is what writers do. We write, get feedback, and rewrite. And as the author who coached us at Highlights said, I CAN do this. And so can you.

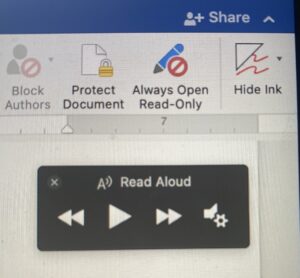

Ever since I made the decision to become a serious writer, members of my family have asked me to edit their writing projects. I have said yes to college essays, business presentations, and even a Master’s thesis. But before I ever agree to do this, I always require the writer use one important self-editing tool – they must read their work out loud! They can read it alone in a quiet room or give a dramatic performance for the dog. It doesn’t matter, as long as they do it. This may sound like a common revision strategy to those of you who have been writing for a long time. But believe me, many people skip this step.

Ever since I made the decision to become a serious writer, members of my family have asked me to edit their writing projects. I have said yes to college essays, business presentations, and even a Master’s thesis. But before I ever agree to do this, I always require the writer use one important self-editing tool – they must read their work out loud! They can read it alone in a quiet room or give a dramatic performance for the dog. It doesn’t matter, as long as they do it. This may sound like a common revision strategy to those of you who have been writing for a long time. But believe me, many people skip this step.

Bill Gates said in 2020 — “Everyone needs a coach. It doesn’t matter whether you’re a basketball player, a tennis player, a gymnast, or a bridge player.” But let’s finish that sentence.

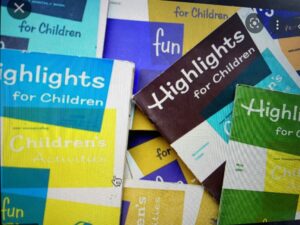

Bill Gates said in 2020 — “Everyone needs a coach. It doesn’t matter whether you’re a basketball player, a tennis player, a gymnast, or a bridge player.” But let’s finish that sentence. I have very strong childhood memories of getting the Highlights for Children magazine in the mail. First of all, it was mail – for me! (And my brothers, but mostly for me.) I’d spot it on the kitchen counter, whisk it off to my bedroom, and immediately turn to the hidden pictures page. Then I’d search and search until I found every last rake, spoon, ice cream cone, and whatever else was listed at the bottom of the page! Today, Highlights publishes entire workbooks of these puzzles. They even have an app.

I have very strong childhood memories of getting the Highlights for Children magazine in the mail. First of all, it was mail – for me! (And my brothers, but mostly for me.) I’d spot it on the kitchen counter, whisk it off to my bedroom, and immediately turn to the hidden pictures page. Then I’d search and search until I found every last rake, spoon, ice cream cone, and whatever else was listed at the bottom of the page! Today, Highlights publishes entire workbooks of these puzzles. They even have an app.

Critiquing is a critical part of the writing process – getting feedback from others gives us guidance and can shed a light on where we might focus in revision. There is so much we can’t see as the writer of our own work and getting other people’s responses to what we’ve written is truly illuminating.

Critiquing is a critical part of the writing process – getting feedback from others gives us guidance and can shed a light on where we might focus in revision. There is so much we can’t see as the writer of our own work and getting other people’s responses to what we’ve written is truly illuminating.